Through her distinct narratives, Bijoya Sawian has brought to the fore Khasi life and culture. Her writings are true to her indigenous roots. They celebrate a way of life which she feels is slowly slipping away from popular consciousness. Her efforts are reflected in her body of work comprising both novels, short stories and translations. Whether it is Shadow Men: A Novel and Two Stories (published by Speaking Tiger) and Khasi Folk Talesor translations, The Teaching of Elders, About One God and The Main Ceremonies of the Khasis, Sawian has immensely contributed to keeping alive the folk traditions and culture of her community.

Recently, the septuagenarian was nominated for the prestigious Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize 2020 for the second edition of her book, Shadow Men: A Novel and Two Stories, thus recognising her work and effort in the field.

A student of English Literature from Delhi University (she did her under-graduation from Lady Shri Ram College and post-graduation from Miranda House), Sawian is gainfully occupied nowadays working on a new book, some short stories and a translation of the traditional Seng Khasi songs. Apart from writing and translating books, Sawian is also an educationist. Settled in Dehradun, she runs a senior secondary school with her husband and sons.

The NEStories caught up with Sawian for a freewheeling chat on her books and her efforts to popularise Khasi culture.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize for Shadow Men?

I am grateful to the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize committee for the nomination. It has taken the book to another level;it is now being read widely.

Shadow Men emerged from a deep sense of responsibility and conviction that if we face problems armed with honesty and understanding, it will bring about change; and this is a massive change in terms of acceptance.

The unrest you saw in Shillong inspired your book. You also mentioned that you ‘dipped into your memory.’ How much research did you do? How long did it take to finish the book?

Yes, it is based on the experiences I encountered, the stories I heard from others and the reports I read in newspapers and magazines — notably a conversation I had with a nephew — who is the character ‘Strong’ in the book.

Needless to say, this is a work of fiction that I have spiced up. For example, there is no incident of a murder in a ‘big house’. However, this extra detail gave me a chance to move the story forward and, even more importantly, allowed me to communicate my ideas clearly to the reader.

The journey of piecing together this book started in my mind in January 1980, and continued till August 2001, when I actually wrote it down. So, the incidents relay the 21 years of continuous bombardment and turmoil inside my mind caused by the violence that continued sporadically, but as intensely, in Shillong.

Finally, I decided to write what I know, or what I think and hope will happen consequently. So, the incidents which stayed in my mind came out strong and flowed naturally; there is no chronological order in the narration. It took me a night and a day to do the first draft.

It all began the night when the militants ran through my parents’ compound and my first reaction was of concern — ‘Thank God the dogs are still in the kennels!’ I thought. My startled sister-in-law Aneeta told me later that I had an opinion which should perhaps be expressed and might be of use. I agreed with her and I did it.

How is the second edition of Shadow Men different from the first one?

People who have read both editions said the second edition feels more complete. All the loose ends are tied up and many unanswered questions are now answered. The first edition is more like a draft, while the second one is an entirely new book.

It is thanks to my readers, and the detailed questions put to me by my publisher Speaking Tiger’s vice president, Renuka Chatterjee, that this book is what it is now. For example, explaining the nuances of a matrilineal, not matriarchal society, was a later development. There were other questions as well. Why did so many people from outside come to settle in Shillong? Why is this so upsetting for the local people? Many readers of the first edition could not understand these aspects of the Khasi community.

Have there been major changes in Shillong since the time you wrote the first edition?

Yes, to an extent some things have changed. Politics has cleaned up a lot since the first edition came out. Chief Minister Conrad Sangma and his team are doing a good job — I am optimistic and happy about this.

How successful have your translations been in bringing forth Khasi culture to the outside world?

The translations have been well received, especially after Vivekananda Institute of Culture published the later editions. That has done a great deal towards sharing a deeper knowledge about the Khasis. Almost 80 per cent of the readers were unaware of the indigenous religion called Niam Khasi or Niam Tre of the Khasis and Jaintias. The Khasi book of Ethics and Etiquette has been especially instrumental in creating awareness. It is secular, universal and relevant even now. I think the translation, titled Main Ceremonies of the Khasis, is an important document, which can be taken up even by scholars and researchers.

For instance, there is a chapter on marriage which came to mind when I learned about a surge in domestic violence during lockdown. According to traditional rules, if the marriage turns sour, the elders meet and try to settle the differences wherever possible. If there is violence in word and deed, and there is no remorse and improvement over a period of time, the couple is advised to separate and necessary formalities are done.

And you translated Ka Jingsneng Tymmen into English.

These teachings have been passed down orally for generations until Rev Thomas Jones, a well-known Welsh Methodist missionary, gave us the Roman alphabet. Radhon Singh Berry Kharwanlang wrote down the teachings, and the first publication in Khasi was in 1900. I translated this literary masterpiece (which contained 109 stanzas) into English in 1997.

Tell us about your childhood. What was it like growing up in a traditional Khasi family?

I am of mixed parentage but I grew up in a traditional Khasi family, one of the few who resisted the wave of conversion in the 19th century. My mother is a Khasi who belonged to one such family that adhered to the indigenous religion and culture.My father,(L) Lala BK Dey, was seven years old when he, along with his parents and three siblings, came from Sylhet (now in Bangladesh) in 1927. My grandfather was a lawyer, so they settled down comfortably, made friends and loved Shillong and its people. I grew up in my maternal grandmother’s home where my father had moved in.

Was it a shock when you moved to Delhi for studies? When you married into the royal family of Himachal Pradesh, did you have to make adjustments?

In 1967, when I was to leave for Delhi to join Lady Shri Ram College, my father and maternal uncles, (L) Maham Singh and (L) Kynpham Singh, sat me down and emphasised on my privilege of having grown up as a Khasi in my mother’s culture, because of which I should always think of myself as a Khasi. He did not want me to have an identity crisis later on in life and, for his foresight, I am deeply grateful.

It worked well with me. Yes, North India could have been traumatic, but those were the days when we used to laugh things off. At first, I did not understand what the big deal was about ‘women’s liberation’. However, when I explained my background to my friends, they realized that I came from a different culture where women were not considered ‘inferior’ to men.

Later on, I married into an erstwhile royal Rajput family of Himachal Pradesh. Interestingly, a traditional Khasi home like mine is so formal that I had no adjustment problems.

What is the one fundamental change that you have noticed in Shillong now as compared to your childhood days?

There are many. When I joined Loreto Convent, I realised that the nuns at school were kind, and yet treated me differently for adhering to ‘pagan’ beliefs. Outside too, window curtains would be drawn when we proceeded to festival ground Lympung Weiking where Shad Suk Mynsiem, our annual thanksgiving dance, was held.

Around 25 years ago, things began to change when people started travelling more and were better educated. Many realised learning about one’s own culture does not take away, but adds to one’s stature, no matter to which religion one belongs.

I strongly feel the change now especially as I hear beautiful hymns sung with traditional Khasi lilt, and as I watch the youth who have no hang-ups about using traditional nuances in art, music and fashion.

How much has your matrilineal background shaped you as an individual and an author?

In matrilineal society we take the lineage from the mother but the head of the family is the eldest maternal uncle. We believe in a system of equality where a man has his space and so does a woman. Nobody is superior or inferior. There is a saying in Khasi ‘A house without a woman is like a body without a soul. A house without a man is a body crippled.’

My identity as a part of this unique Khasi matrilineal society has strengthened my sense of responsibility as a representative of a minority communityand encouraged me to preserve all its glory.

Do you think we need more authors from the Northeast to come forward and share their stories?

Yes, and more importantly, after they are published, they should be promoted, reviewed and widely circulated to encourage a large readership. We need publishers and reviewers who will understand the importance of our work and see the larger picture. I got very lucky with my publisher Ravi Singh. He is amazing

Is there enough literature coming out of the Northeast?

No. There are many talented writers and poets in the region but they lack contacts with big publishers and other writers. As a community, we are either bashful or too proud to beg. I know of a few who have incredible stories but are hesitant to write about them. Maybe, it will come in good time.

Do you think the youth in the Northeast face a cultural void?

I will only speak for what I know of Meghalaya. In the 19th century, the missionaries came, and indigenous faith was replaced by Christianity. To me, all religions are essentially good and have the same foundation, which is truth.

In the Khasi and Jaintia hills, I wish the missionaries had not thrown the people into a cultural vacuum by making them ashamed of their indigenous culture, which extended to even basic ethics, names, attire, and music among other things. Instead, there could have been a fusion of the two.

In Mizoram and Nagaland, on the other hand, people still go by their traditional names, wear their outfits with pride and perform their dances with dignity. But not so in Meghalaya. So, even after two centuries, people are still grappling with this trauma. The youth understand this, but it is not easy to reconcile culture as part of one’s identity. How can you, when you have been told that indigenous symbols are regressive, pagan or a manifestation of the devil?

However, all is not lost. Recently, some of my Christians friends sent me videos of songs which had the traditional lilts, and some have bought copies of The Teachings of Elders to read to their children and grandchildren.Traditional drums are being played in some churches. I see all this as a Renaissance — the cultural revival of my people. The radicals amongst the Niam Khasi believers, of which I am a part, are not in favour of this fusion.

Are there any news books or translations in the pipeline?

I am now working simultaneously on a new book, some short stories and a translation of the traditional Seng Khasi songs. I keep shifting gears according to what I am inspired to work on at a particular moment of the day. While lockdown has been spent productively, I do feel we should all take this period as a time for healing and introspection.

What other work have you been involved in besides writing?

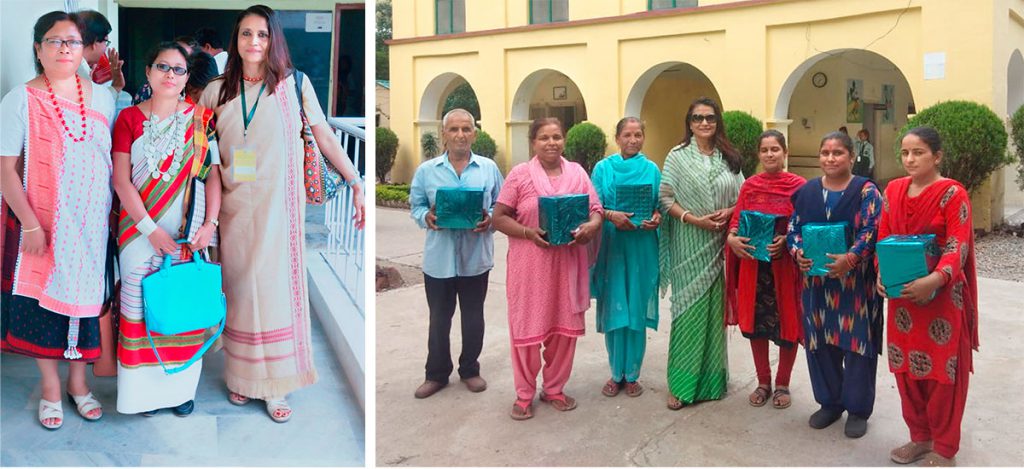

I am passionate about education. My husband, Alark Singh, my sons and I run a senior secondary school in Dehradun. Both sides of my family had been involved in education since the 19th century. My maternal great grandfather, Jeebon Roy Mairom, brought higher education to the Khasi hills in 1878 and my paternal great grand-grandfather, Lala Prasanna Kumar Dey, started Jubilee High School, one of the first schools in in Sonamgunj in Bangladesh, then part of Assam, in 1887. I share my ancestors’ belief that education is the best gift one can receive and give.