“Elephant!” I screamed looking out of the car’s window. The driver screeched the vehicle to a halt. The brownish-gray loner, swaying leisurely, emerged from the forest thicket onto the road creating quite a flutter. Nervous forest officials frantically stopped vehicles to let it pass, lest this wild and unpredictable loner got agitated. This was my umpteenth wild elephant sighting en route to a tea garden.

Since childhood, the long drives to visit my tea planter uncle in a new tea estate every few years have been reassuringly eventful. Crossing acres and acres of lush green tea plantations on each side of the road for miles, my smog laden metropolitan eyes are always witness to some adventure or the other: be it wild elephant and leopard sightings in the muggy tea estates of Assam, or steering through edgy hairpin bends in the mist enveloped plantations of Darjeeling, or sometimes stealthily crossing nondescript villages caught in political tensions.

The tea garden could be anywhere but once the car hits the gravel road of a tea bungalow’s compound, you know a world awaits that hasn’t changed much. A charmingly old world that has managed to retain its vintage grandeur in those sprawling wooden bungalows, just like how the burra sahibs made it and set it up as a way of life during the British Raj.

It has always been late evenings by the time I’ve reached a new estate tucked far away from the hustle-bustle of civilization. My uncle, the burra sahib of the tea estate waiting in the extensive jaalibaari or the wire-meshed verandah in the rhythmic cacophony of the night insects. The jaalibari in most tea bungalows is done up in exquisite wicker furniture and is the casual meeting room, offering an expansive view of the manicured gardens and the plantations. Often the burra memsahibs or the wives of the tea planters host their high tea afternoons for the other memsahibs from the surrounding estates in the jaalibaari as their husbands, who are ‘sophisticated farmers’ like my uncle likes to call himself, are away at work.

The best part about being hosted in a tea bungalow is the period look which has been maintained over the years. The polished teakwood and mahogany colonial furniture made by the best Chinese carpenters in the days of the Raj still stand adorning formal drawing rooms, guest rooms and dining halls. And when it comes to hosting guests, the tea garden bungalows can compete with the professionals hands down. Their guest rooms usually are a full suite comprising a private drawing room often opening out to the garden, followed by a bedroom where the writing desk takes centre stage along with an airy dressing room and a massive washroom. The guests are customarily welcomed by tea served in the proper English way along with some homemade cakes and cookies by a uniformed bearer rolling in the paraphernalia on a tray trolley.

On my last visit to a tea garden, over drinks and cocktail snacks at the tall wooden bar tucked in a corner of the jaalibaari with the gecko’s croaking in sync with the country music playing, I asked my uncle out of curiosity, “When did tea actually come to India?” I had assumed, we, being a chai drinking nation primarily, it must have been a long time ago. To my surprise I was told that tea was introduced to India, the largest consumer of tea as of date in the world, only in the early 19th century, as late as 1835 CE.

The Chinese were first to consume tea as a medicinal drink from the plant Camellia Sinensis, native to China around 5,000 years ago. Somewhere around the 6th century, the Chinese discovered that the infusion of the wild tea Camellia leaves could become a palatable beverage if its leaves were carefully processed. From the end of the 8th century onwards, China had turned into an exporter of tea which was carried by porters across the trade routes to neighboring Tibet and Mongolia and then the tea caravans took it further to Japan and Russia. The merchant ships of the Dutch East India Company brought the first tea to Europe in 1610 CE; the Europeans took to tea instantly.

My tea history knowledge was further enhanced by a beautiful book that I was handed, A Journey in Time – Pioneering and Trials in the Jungle by John Weatherstone, a former English tea planter. As I flipped through the book, it revealed interesting trivia: “The first authentic manufacture of tea was written by Lo Tsu in about 780 AD. It is said that the Emperor of China and his court drank a special tea which was harvested from wild tea Camellia trees that grew so tall that it could be plucked only by monkeys. Each season some 200 pounds of Imperial monkey-plucked tea was produced.”

Regarding India, Weatherstone writes, “By the 1830s, the demand for tea grew rapidly. It was exported (from China) to Europe, Great Britain and America. East India Company was then interested in the possibility of growing tea in British India. In January 1835, the Port of Calcutta saw the arrival of 80,000 tea seeds which were sent to botanical gardens for germination. From the original consignment of 80,000 seeds, resultant 42,000 young plants were distributed between three trail regions – Assam got 20,000 saplings, Kumaon got 20,000 saplings, Nilgiri Hills in South India got 2,000 saplings. Jungles were cleared and the tea saplings planted. Chinese artisans, skilled in the cultivation of tea and its manufacturer were brought. In the end of 1837 the first samples of tea made from Indian tea tracts was sent to Calcutta and subsequently to London. Twelve chests were sent. Tea was sold in London (tea auction house) between 16 shillings (80 pence) & 34 shillings (1.70 pounds) a pound in 1839 and it was phenomenal.

Later, much after plantations in Assam and Darjeeling came up, the jungles of Terai, known for their scorching heat, malaria and tigers, were seen as a possible terrain for plantations. Makaibari and Selin Tea Gardens were the first to be opened in the Dooars in the early 1860s. Out of all the areas where tea plantations were initially explored, Assam has grown to be the largest tea producing state in the country with plantations mostly centered around the districts of Darrang, Dibrugarh, Lakhmipur, Goalpara, Kamrup, Nagoan, Sibsagar, Cachar, Karbi Analong and North Cachar.

The discussion on tea that day had continued late into the night over dinner, shifting from the bar to the dining hall where as usual an elaborate multi-course spread, a mix of Indian and Continental food lay on the dining table perfectly set in formal crockery and cutlery. The veggies on the table had made their way from the baari, the bungalow’s vegetable garden; truly organic vegetarian food served casually without the ‘organic’ hullabaloo tag of city slickers .We wrapped up our meal with a sinful in-house Blueberry Cheesecake made by my aunt, also a former tea planter.

Far from the bustling cities, the tea bungalows stock up well on their kitchen rations and everything is made in-house; from breads to cookies to cakes to jams to all the delicacies. Most of the burra memsahibs, too, are an expert in confectionary often displaying their skills at high tea afternoons or sometimes at parties hosted at the Planters Clubs scattered all across the tea plantations.

The Tea Planters Clubs have been there from the days of the Raj and are known for their lavish parties with great food, wine, music and dance. After all, for the planters staying in the wilderness far and cut off for long periods, it can get a bit lonely. But the Clubs ensure they socialise and let their hair down. It also keeps them fit with a host of sports to engage in: golf, tennis, squash, football and billiards are among the favorites with regular inter-club competitions and events. The Clubs also keep the memsahibs occupied with events like flower shows.

All tea plantations are skirted by troughs for excess water drainage and those in Assam and the Dooars are shaded by trees planted sporadically amongst the bushes. These shady trees ensure that the tender tea leaves don’t burn from a direct sun. The tea bushes are regularly pruned because the Camellia Tea tree, if allowed, can grow up to 60 feet tall. Each plantation has a seed bari that incubates new saplings for fresh plantations.

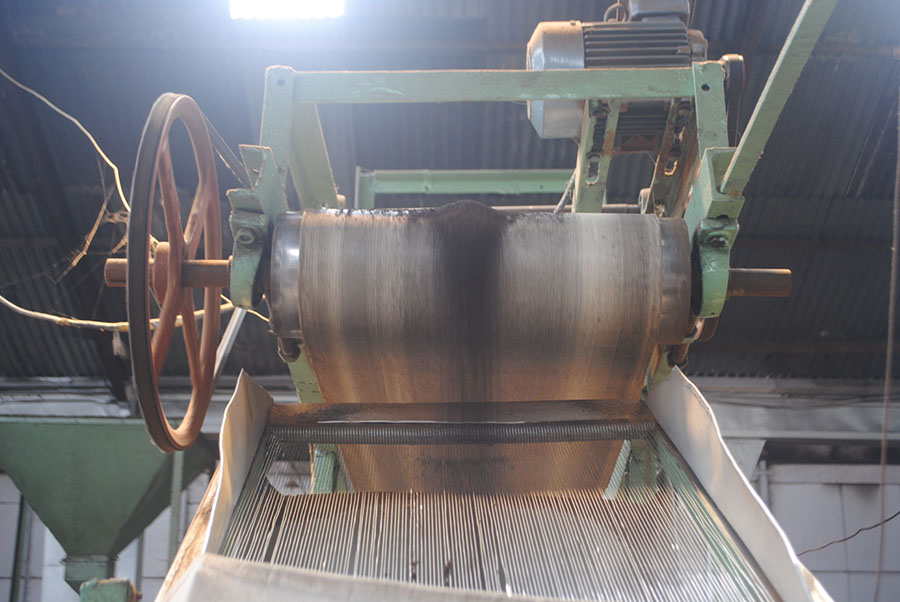

The process of turning tender new tea leaves into granules ready for making a pot of tea is a fascinating one. It starts with the pluckers depositing the plucked leaves which are put in long trays to wither and then cut and rolled in huge rollers. They are sent for fermentation and then again dried and rolled in dryers to further travel on belts to be sifted and sorted as per the rolled leaf size into different tea grades. From the best tea grade to the tea dust that lies in the end, each category is then packaged and sent for price auctioning. The tea taster of the factory religiously sips several cups a tea a day from neatly lined cups to test each day’s production for aroma, colour, grade and taste among other factors.

After snatching moments of living partly the life of the tea planters, leisurely weeks soon end, forcing one to head back to the noisy city. And every time I bid adieu to the crossing purple flowering Azaar trees dotting the highway framing the lush tea gardens, I tried locking in the smells, sounds and images of this beautiful countryside whispering under my breath, “till we meet next time.”

Nanditta Chibber is an independent creative consultant and writer. Between projects and her travel jaunts, the life lived, witnessed, imagined and fantasized gets inked when she sits on her haldi yellow study table