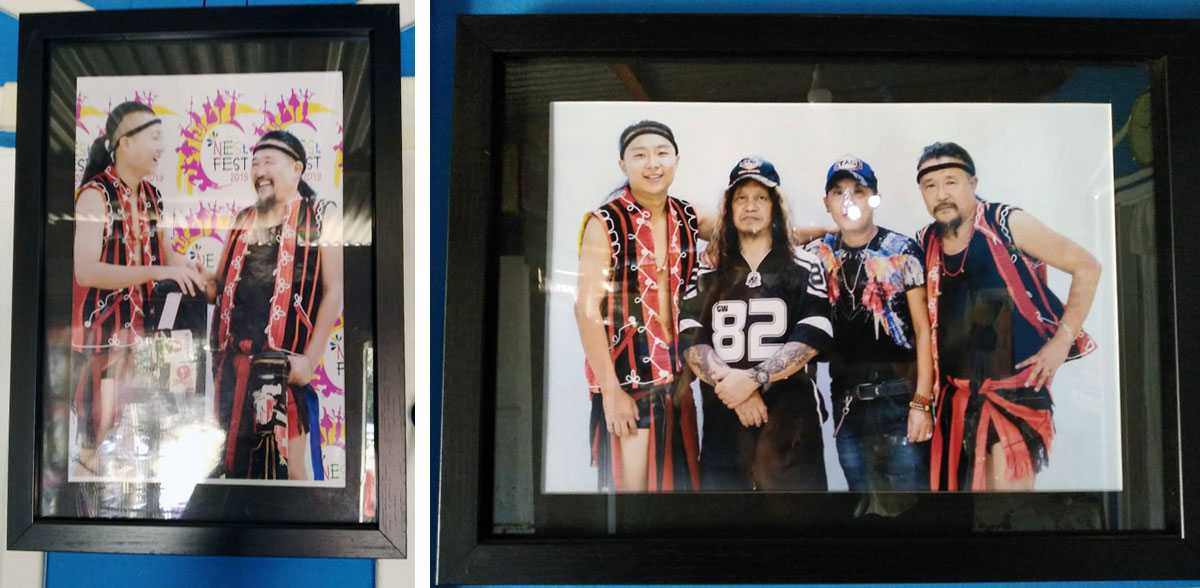

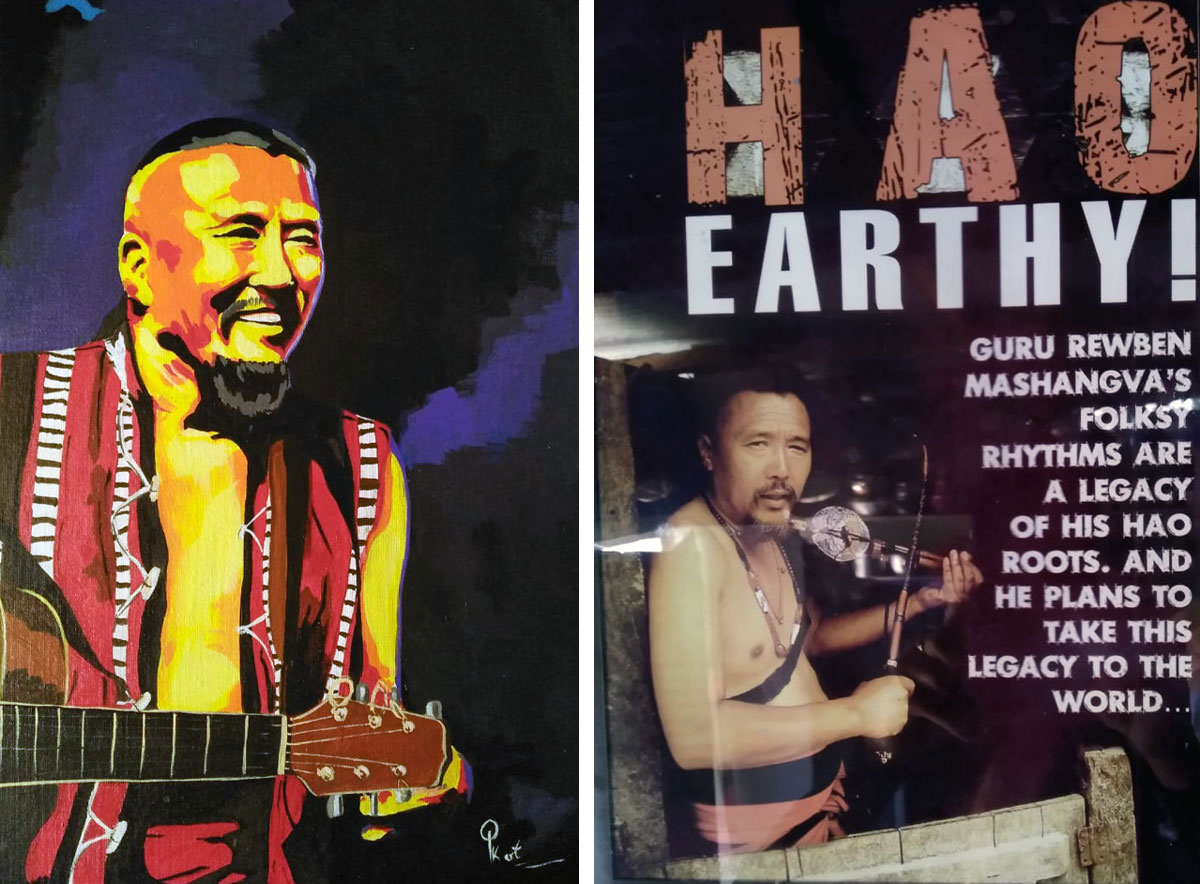

Mr Tambourine Man: Guru Rewben Mashangva

Guru Rewben’s signature “Naga Folk Blues" is a blend of Tangkhul folk medley with guitar riffs and Western folk...

Weaving traditional Tangkhul folk into guitar riffs inspired by Western folk artists combined with a creative process pioneered a new musical language, which he calls "Naga Folk Blues"

Hawkers selling fresh vegetables; small second hand shops; bakeries and more dot the street leading to Nagaram locality in Imphal. Once inside, it’s easy to locate the home of one of the most well-known musicians of the state. And be sure to be serenaded by music and singing ranting the air. Neighbours are used to it. And there is simply no question of complaining. The silent wee hour of the day is when Rewben Mashangva keeps a date with himself – he picks up his self-made instruments and croons. Mashangva’s soulful music is soothing, relaxing, meditative and far from being a ‘noise’ in that sense. Each time he is engrossed in his music meant that he is ‘away from the world.’ And that occasional escapade into another world is what fuels his soul.

So, one early March morning almost a year after the lockdown, we tracked down the musician unwinding at home. He’s outspoken, free spirited and down to earth. The self-made musician, songwriter and singer, who was conferred the title “Guru” by the Ministry of Culture (government of India) in 2004, is upbeat as ever.

Even though he never had a formal training in music, it was his sheer love and passion for music that got him to dig deeper into his roots, folklores and cultures. And that explains the depth of his music. And his audience spans across India and overseas. Each time he travels, he has what he calls a portable museum – a bag that has his musical instruments – a guitar, a bamboo flute, few of his traditional clothing and personal belongings. Be it in China or across African countries, for performance at diplomatic events, the musician clings on to the bag calling it his only possession in the world.

Born and brought up in Choithar, a charming village in Ukhrul district, east of Manipur, he carved and created musical instruments from household items. Mashangva's destiny was thus manifested even as a boy. What village life deprived him of in terms of education and formal musical training, was made up for in great measure by the Guru's undying passion and the wealth of folklore and love for music that surrounded him - at first, Mashangva had only his roots, his family and community to rely on for his source material. His music is his tribute to all those who brought music into his life - an old friend who introduced him to Bob Dylan, the folk legends of the 60's and 70's, his father who taught him the art of creating bamboo instruments and, most importantly, the future generations to whom he wishes to pass on this intrinsically community-centred passion for traditional music. He would often sit among the village elders, weaves traditional Tangkhul folk into guitar riffs inspired by Western folk artists - Mashangva's creative process pioneered a new musical language, which he calls "Naga Folk Blues".

Guru Rewben in this free-flowing conversation with NeStories delves deeper into his new language of music - the universality of which is visible in the crowds that chant along with him - the words passed on by the village elders of Choithar.

President Kovindpresents Padma Shri to Guru Rewben Mashangva for Art. He is a Naga folk artist and musicologist. He has also been working continuously for the conservation of the environment, conflict resolution and other social humanitarian causes. pic.twitter.com/lY8eT93bLA

— President of India (@rashtrapatibhvn) November 9, 2021

Padma Shri is prestigious – does it give you a sense of recognition?

I got a call informing me about the award beginning of 2021. I felt good knowing that my music is being finally recognised. Indeed, that in itself is a great feeling.

All through your childhood, you were searching for music in everything that surrounded you. Take us back...

I was born in 1961 and the only school then in my village was Choithar Government School in Chonithar village in Ukhrul district. I remember vividly that we had only three classrooms. We did not study English, Hindi, or even Manipuri (Meiteilon). We were taught in our native Tangkhul language itself. My father was a carpenter, and I would assist him in whatever he was doing. He often sang and played notes with his mouth on the bamboo trumpet which he made himself. I grew up with the folk songs which I heard from my father, from the villager elders and traditional folk singers.

I could not sing well - I felt my skills were never up to the mark. Of course, everybody sings in the village Church. I, too, participated in the Church choir of Choithar Baptist Church. My dream was to become a singer – that too, a good one.

Even if we, simple village kids, were interested in music or, say, wanted to learn to play the guitar, there was no one to teach us. Also, we had no money to buy a guitar. We used to set up our own music – making music out of used tins, and drumming beats with a stick or a cane.

Till today, I haven't been to any formal school of music. I learnt from my home, my village, my elders and our folk singers. All that I learnt from them is stored in my head - not written in any book.

How did Bob Dylan’s name and music come to be a part of musical journey?

It was in the early 1980s. My friend, Matpham Luikham who lived in Bombay then, used to bring his tape recorder and cassettes whenever he visited home. I would go to his house to listen to songs on his recorder since we didn't have one at home. We would sit and chat with Bob Dylan’s’ music in the backdrop. He insisted that I listened to Bob and practice. He would translate the songs for me. At that point of time I could not really follow Bob’s music - it was difficult for me. I would sing my own songs - funny ones. Nevertheless, Matpham would tell me “it is good”.

Matpham was a good artist who painted the name of the famous Bollywood film Bobby. He was the one who encouraged and inspired me to pursue music. I owe him a lot. He is no more. How I wish he could have witnessed all that I have done and achieved till now.

How did you find yourself – your thirst for music and what did you do to get there?

I got married in 1990. Now that I was married, I had to start earning. I came down from my village Choithar to the state capital of Imphal to begin work at a small private bank as a clerical staff. However, after working for five years, I said to myself “enough”. I could not get any satisfaction out of any work that I did. So, I finally told my wife “I don’t know what I will do, but I am quitting my job”!

So began the journey of finding myself, my songs and my music. Back then, all that I had were my folk tales and folk songs, and one acoustic guitar.

Curious about music, especially traditional music, I wanted to know more about our folk-lore and folk music. I did a lot of research – meeting village elders, discussing with them and learning from them. Slowly and surely, it happened on its own, and the music eventually started to evolve.

When did your big break happen?

My first public performance was at a public event organised by Naga Student Federation in Ukhrul. I requested them to give me time to present one song. I performed a rendition of Bob Dylan’s number Trust Yourself, with a folk melody. The response was amazing. Next, I performed in Kohima, and then it just went on from stage to stage.

I only had three song numbers prepared in those days - Trust Yourself, Deep Breath and Burning Sky.

How did your music evolve? Tell us how Naga Folk Blues came about.

There were problems and roadblocks along the way. Ever since I started performing in public, people would ask me to play or sing folk songs in other languages. I could not do that because I didn't speak Hindi or Meiteilon. I don't even speak English well, nor do I write. I only performed in Tangkhul dialect.

To add to this, I felt that singing our forefather’s folksongs would not be original or authentic. If I sing in English that too would just be an imitation. I tried hard to imitate other singers before me, but neither did I sound like the original, nor did I possess the style of traditional folk or Western blues artists. I found myself dissatisfied with my own work. More so, I did not want to simply imitate or copy those who were already established singers.

At the end of the day, I realised that the general public is not too keen on listening to the folk songs that I played, when there are already popular folk singers out there.

To find something unique - something that sets my music apart, I knew I had to create my own niche.

So, I began to compose my own songs, based on the research and learning from elder folk singers of Choithar. This was how the new language - I call it “the Naga Folk Blues” - was created. It is basically a synchronized folk and Western blues style. People accepted my songs, and now they call me the “Father of Naga Folk Blues.” Owing to its unique character, this new language gained immense love and popularity - the response is overwhelming.

Fusions are not unheard of in the music business - where does the unique character of "Naga Folk Blues" come from?

It takes the collaboration of many people - and finally a lot of time and practice to piece everything together. I often invite elders to help me. Sometimes, I connect with writers and school teachers. The Naga Folk Blues is an ongoing process – my main aim and the idea behind it is to present it so that people listen and like the music.

I jazz up my folk songs by adding my guitar to it - keep on creating and finding ways to better it. It took me 30 years to master the guitar for my folk songs. To master the flute that I made by myself - it took me over seven years.

Another unique feature of my songs is that they are not written. The medium is oral. The lyrics are my expression derived from folklore and the melody is loyal to the “blues” style.

Only after mastering both parts of my songs do I perform in front of people. Moreover, I only perform for small, intimate gatherings, rather than some extravagant public concert.

How has your music impact your children?

I have four children. My youngest son, all of 19, performs with me. I often take him along with me when I am performing. I managed to pass on my knowledge to him, but it is up to him to continue making music if he so desires. More importantly, I take my son wherever I go, in order to expose him to the outside world so that he may experience what life is like beyond our village and state.

What drew you to folk music? Any vision or initiative for the future?

I have always been disturbed by the fact that there will come a day when our predecessors will be no more, and a new generation will take their place. Even today, the older generation of folk singers, say, from the 1960s or 1970s, are no more. Perhaps, I may be the last from my time. There are so little remnants of them, of the past, and especially of the folk music that is deeply rooted in our heritage and culture. Even these seem to be disappearing.

What I learnt from those before me - I blended it into the Naga Folk Blues. I believe this is one way of preserving their legacy. Also, in recent years, I have come to realize the need to write down a few of my songs. I requested my literate friends - village school teachers and local youths to record the lyrics to my folk songs. When songs are immortalised in the written form, it provides future generations a solid document to learn from, if they do take up an interest in it. My songs are not meant to be kept in a book - locked up in a box in some museum!

In my opinion, there is a need to cultivate the practice of preserving our old traditions - music is a great way to do this. Teach a song or two to your children - this what I am doing. Our elders, our forefathers have been so hardworking - toiling throughout the year, and yet they have a song on their lips and music in their heart. In comparison to today's world where everyone is busy working in the offices, going to schools and colleges - there is much lesser physical labour, but we do not have time for songs of our own. So, my idea is to start with at least one or two songs.

What are some of the instruments that you use for your folk blues?

I have my acoustic guitar and my trusty home-made bamboo flute called the Yangka Hui. Then, there are the Tingteila (stringed instrument) and Cow-bell.

I am not too fond of electronic instruments. I do not want to depend on electricity. It is unreliable - for instance, once the power goes off in the midst of your performance, you are rendered helpless. I believe the real art gets lost among the artificial sounds.

Where is the place of folk music amidst today’s popular music?

Modern music, or popular music, is very powerful. It is difficult for folk singers and musicians to survive. It is not a profession that guarantees a regular income. Not only limited to me - the problem pervades the country. Besides the financial issues, the new generation does not seem too interested in folk.

Earlier, people would call me “crazy” and “mad.” I ignored them and told myself “I am 20 years ahead in thinking”. Today, people have started imitating my hairstyle, and notice me for crafting my own instruments and designing my own outfit for stage performances.

Has collaborating with other fellow musicians add to your canvas?

Indeed, yes. Raghu Dixit and I did work together for the song Masti Ki Basti, which we recorded in 2011 for the first season of The Dewarists (a musical television series on MTV India). We performed together live at the Autumn fest in Shillong as well.

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown I composed some songs, including Stay Strong Wuhan. As for future plans, let’s see how the world turns out post the COVID-19 pandemic. Although I do know deep down that it is part of the natural process of ups and downs. It will heal with time.